TOPOLOGY AS

RELATIVE DISPLACEMENT

Pablo Lorenzo-Eiroa

Andrea

Palladio has been identified as a mannerist, since his work

resisted previous canons and the architecture of the

renaissance that was obsessed with linear order. This

resistance included the displacement of order in plan and,

later discussed, the interruption of perspective in

elevation. This resistance is interpreted from a reading of

his architecture, based on the establishment of an order but

also its critique. Palladio incorporates an a posteriori

displacement, a variation that would critique the initial

predetermination of the order he establishes. With this

critique, Palladio anticipated the work of Borromini and

many posterior architects, since even if his project seems

not to suspend the pendulum between the past renaissance and

the baroque to come, by critiquing the predetermination of

order, he anticipates a conflict between predetermination

and post-determination building a continuity between the

two. What is interesting in regards to a post-historical

manifesto, is that his project was arguably one of the first

to both define and also critique a continual cultural

problem in humanism.

Palladio

defined a modern project based on structure, that is based

on the recognition of absolute idea order, identified by the

humanists of the time. This modernism was based on an

advancement from Leon Battista Alberti system of

measurements, which Palladio used to establish a system of

relationships between spaces, assigning continuity across

the composition through alternating rhythmic mathematical

ratios. He reinforced a general logic, not only relating

part to whole, but creating a responsive structural system

that can be both referenced and altered, subsequently giving

an underlying sense of control to the organization. While a

normal proportion is kept constant, the other varies by

inducing displacements to this initial reference, projecting

a relationship that is both kept, accumulated but also

displaced. This system of relationships systematically

controls decisions based on proportions parameterized by

mathematical progression, but particularly developing a self

referential modern consciousness. This mental consciousness

critiques the ideal, generic, typological set of

pre-established relationships incorporating variations to

the composition with singular displacements that activate

specific architecture problems that respond to the logic of

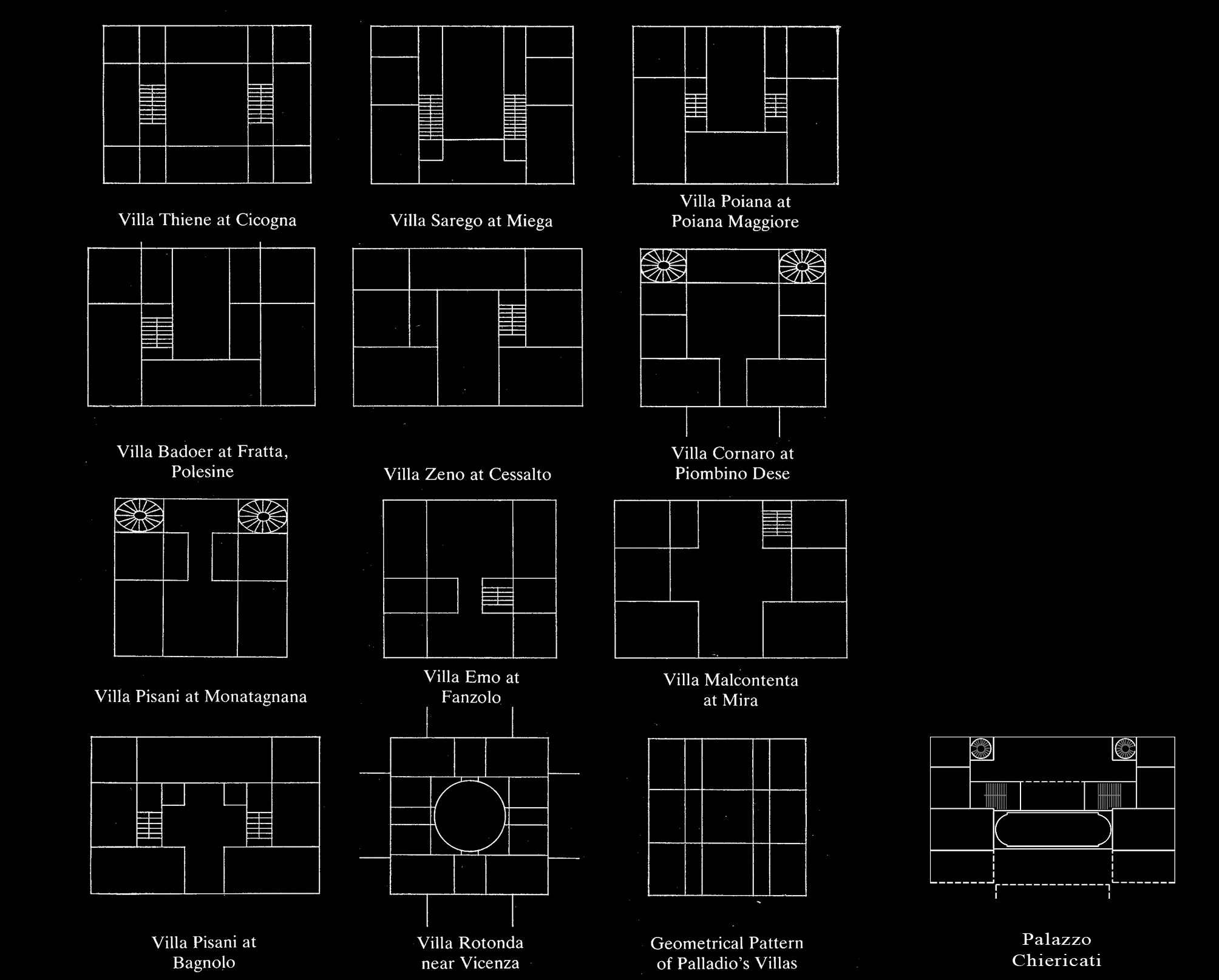

the particular. This systematic work across Palladio's

villas is demonstrated by Rudolph Wittkower's common nine

square grid composition.

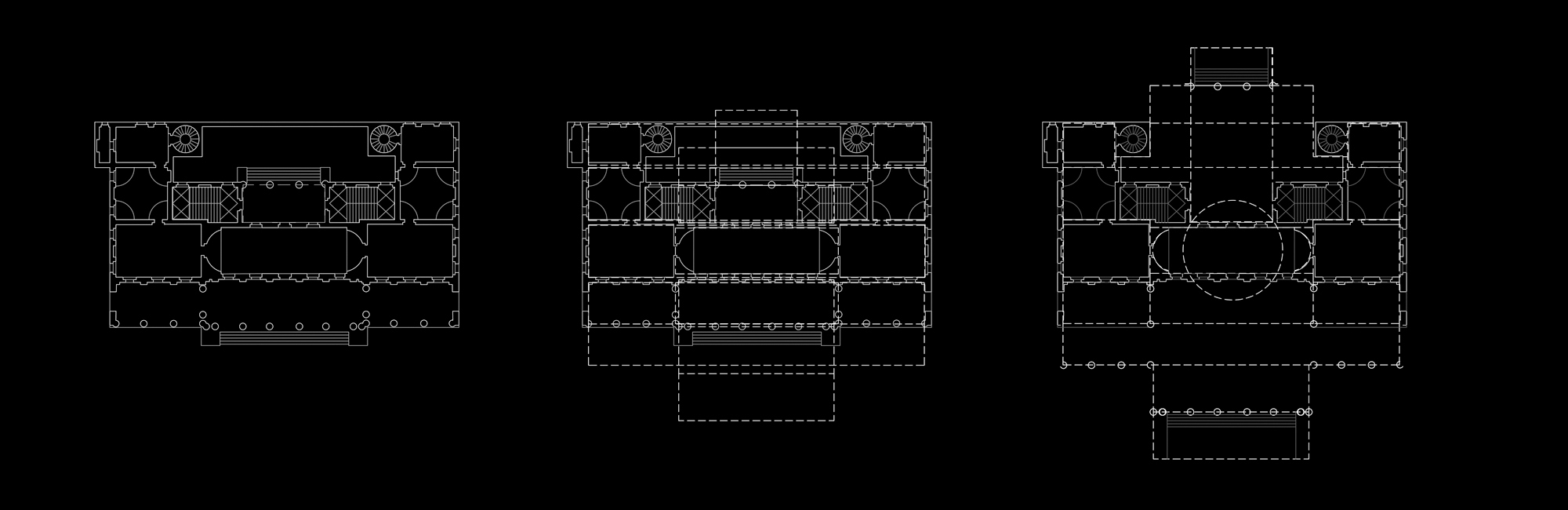

An

alternative projective topological exercise on Palladio’s

Palazzo Chiericati may offer a parallel argument to Peter

Eisenman’s diagrams. The first characteristic of this

building, according to James Ackerman, is its disproportion.

Spaces are longitudinal and narrow due to the compression of

sequential spatial layers perpendicular to the main axis,

which are organized in a distorted nine square grid figure.

This disproportion forced by the constraint of the site, but

independently from indexing this circumstance, it activates

a more relevant organizational problem. The building is

sited on what was the edge of Vicenza. The placement is

quite particular, as a concession by the commune, arguing a

benefit with the public loggia, allowed Palladio to build

beyond the site, placing this particularly designed loggia

in public grounds.

These

series of displacements that relate horizontal to vertical

in the floor plan develop an alternative idea of

architecture topology, since one may reconstruct the

relationship between the original type and the final design

in a continuous elastic diagram, a genealogy of dynamic

forces that accumulates traces. Furthermore, this

topological transformation enables such displacement that

critiques the initial ideal nine square grid organization

proposing a distinct typological change, displacing the

organization from a centralized singular organization to a

field of layered spaces with no hierarchy. This critiquing

of the initial scheme is developed in an intrinsic to

architecture operation. In addition, the design

ultimately seems to tension spaces apart from the elastic

generic organization. The design of the spaces acquire

certain autonomy from the generic relational logic, and even

if one may trace this formal genealogy, the composition is

not reversible, adding tension to the organization.

It is

interesting to question why Wittkower, did not include such

an extreme variation in his eleven paradigmatic diagrams.

Independently from excluding categories (palazzo-villa) his

reductive method forced him to include only variations with

a differential change of degree and not such radical

and conceptual typological change, which establishes in the

series a specific to architecture differentiation.

There are some clues that can give certain argumentation to

this idea crossing categories between villas and palazzos.

One is the location at the outskirt of the town looking at

the landscape, as the openness of the facade makes this

Pallazzo relate to the porticos of the villas. But a more

relevant curiosity may be that in

Quattro Libri he

placed Villa

Rotonda in

the section on palaces rather than the one on villas.

[...] Partially published in Instalaciones: Sobre el

Trabajo de Peter Eisenman and some of the conclusions of

this analysis provided the ground for the Yale Constructs

Spring 2013 article on Eisenman's Palladio Virtuel.