RAINALDI’S

TOPOLOGICAL DISPLACEMENTS [...]

Pablo

Lorenzo-Eiroa

The work of some

baroque architects may offer interesting relationships in

the displacement of the referential spatial structures of

the Renaissance and, as many historians have pointed out,

relate to the contemporary pendulum state of expansion of

architecture.

Bramante’s San Peter’s innovation is due to the motivation

of space as a positive figure, thanks to the intricate

articulation between concave voids and convex poché-walls,

activating a metaphysics in space through the pulsation of

form, assigning an equal value to the void and to the mass.

Borromini made this evident in San Carlo alle Quatro Fontane

(1665-1667) as he pragmatically engenders his philosophic

concept of Res-Extensa performed firstly in the cloister

(1634-1637) where the concave corner is inverted into a

convex figure that indexes a space from outside [fig. 00a].

The interior (1638-1641), presents the corners as a presence

of absence (only straight line in the composition) as a

removal of the corner condition, which affects the stability

of the structure of the space, a metaphysical absence in a

sinuous movement that results in a space that becomes a

continuous positive figure, a unity and a new synthesis, an

innovation that derived into a new canon. As such, it

displaced the archetypical condition of the corner creating

a new language based on a plasticity unfamiliar to the

tectonics of its contemporaneous architecture. Relative to

this question, this building is simultaneously organized by

two systems: one that displaces a centroidal organization

through two centers that transform the dome in a distorted

oval form with a linear direction, and the other conformed

by a nine square grid figure that index the crossing of two

axis [fig. 00b], one expanded and the other compressed,

unified through a continuous spatial gradual degree change,

considered within this context, a topology. This pulsation

indexes the plasticity of an abstract immaterial white

space, the presence of these forces articulate a

psychological awareness in the conception of the space, and

this pulsation is articulated with the rhythm recovered by

the nine square grid organization of the columns that

ambiguously integrate the directionality of space developing

a continuity between the two axis that fuses into a

longitudinal space.

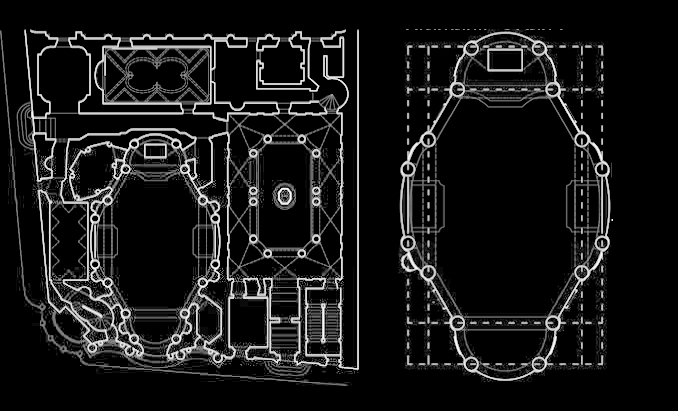

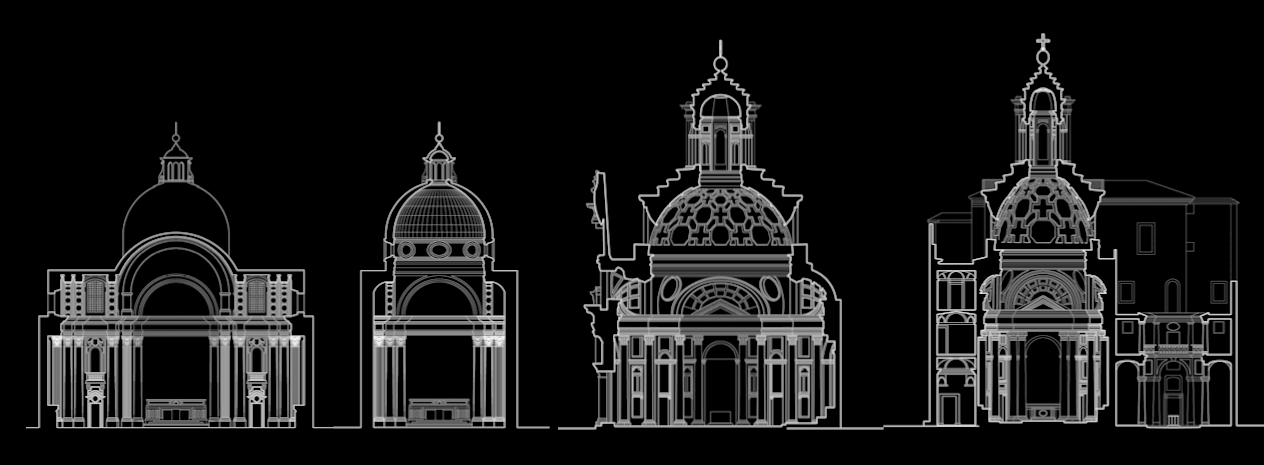

This work was

continued by one of Borromini’s collaborators, Carlo

Rainaldi, particularly in his masterpiece Santa Maria in

Campitelli (1656-1665) [fig.01a, 01b, 01c]. Wittkower

analyzes multiple aspects of this paradigmatic building that

escapes any stylistic category and reaches to conclude

certain influences that provide a ground for this

investigation .

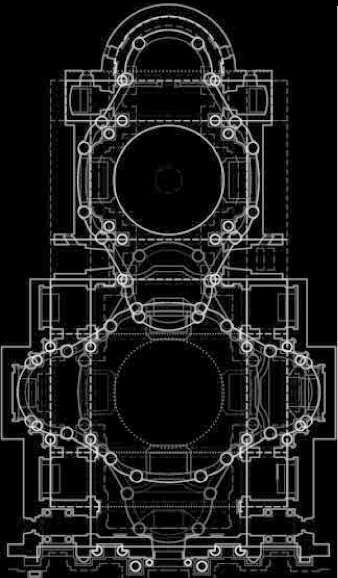

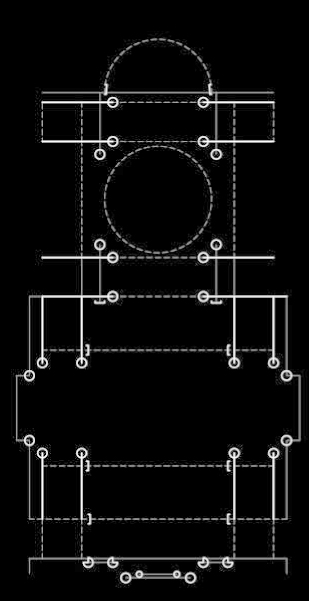

First, the structure of the church of S.M. in Campitelli[1]

is divided in two and it can be analyzed from a critique to

Borromini’s San Carlo, as it indexes two of its floor plans

organized perpendicular to each other, but restructuring

their idea of pulsation and continuity [fig.00b, 02].

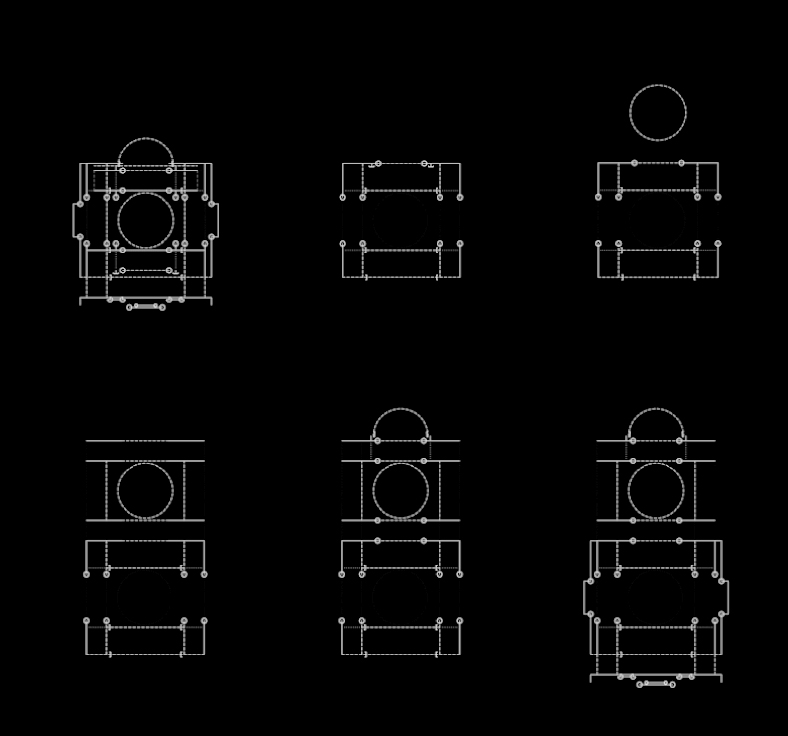

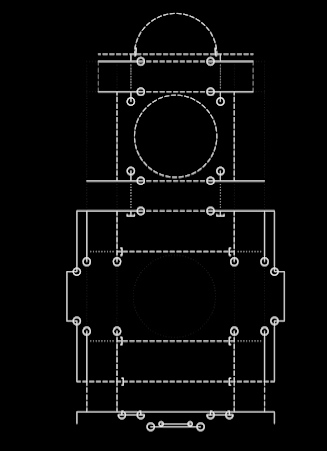

Second, the

anterior space may be read as a Greek cross type that

indexes a small previous church[2] (1658) [fig.03]. The

displacement of the dome and the altar [fig.03a, 03b]

towards the back generates a series of inversions between

the two centroidal spaces that through double negations

surpass a dialectic[3] [fig.03c, 03d, 03e].

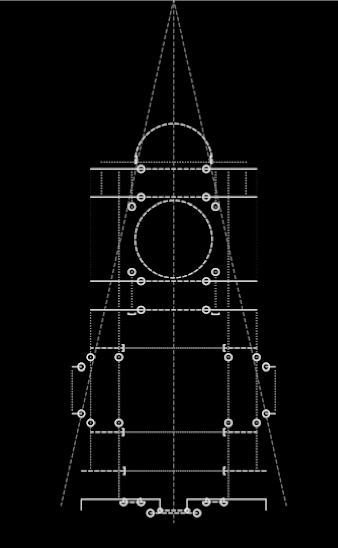

Third, the

processional axis is interrupted in the middle, where the

nave and the posterior space change scale in section and in

plan responding to the site constrain that is coordinated

with the telescopic perspectival focus towards the altar

[fig.04]. Also an interruption in plan originally drawn by

Rainaldi similarly to Palladio’s Il Redentore, indexes

another perpendicular axis as a lateral entrance to the

church, as in the other cases of Borromini, splitting the

church functionally and in the middle.

Fourth, both spaces are based on a nine square grid

organization type since a series of topological –as gradual

displacements- index one with the other (including site

adjustments): the anterior space expanded and the posterior

space compressed. The posterior transversally compressed

space, negates the transept that is supposed to be at the

intersection of the two directions and below the dome that

is left at the anterior space as in a Greek cross

composition, but also referencing Borromini’s tension in San

Carlo’s between the transversal and longitudinal sections.

In Campitelli these two sections, the compressed one and the

expanded one, are parallel to each other composing the two

transversal sections of the building [compare fig.05a and

05b by Rainaldi and fig. 05c and 05d by Borromini[4]].

More importantly,

this “topological” continuous transformation originated as a

displacement of the original structure, originates a

typological change between the two spaces: the anterior

space reinforces the transversal direction, since the space

seems to orient primarily interrupting perpendicularly to

the processional axis with the two lateral altars; the

posterior one reinforces this processional axial direction

with a lateral transversal compression, hence becoming

frontally oriented towards the altar and in coordination

with the vertical presence of the dome, which as such is

indexed but negated in the anterior space [fig.06a]. Both

spaces are contained in a composition that produces a

synthesis among two structures in tension. The perpendicular

axis in the posterior space (dome space) acquires presence

by being negated (double negation) since rather than

presenting lateral altars, abstract emptied walls are

integrated by a curvilinear movement of continuity that

widens the compressed space, as it happens in Borromini’s

S.M. Sette Dolori[5], coordinated with the dome, projecting

a somatic memory in a bodily affection of the previous

experienced space.

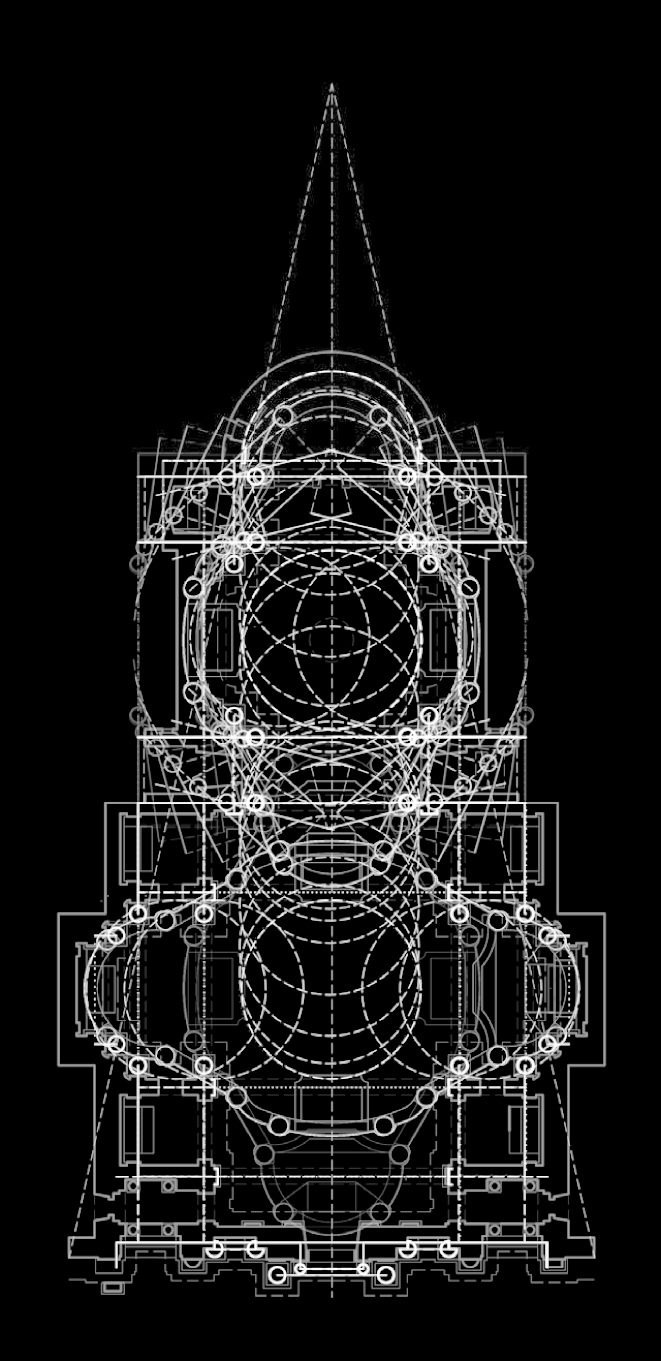

Fifth, these simultaneous displacements present themselves

continuous due to a telescopic folding of space, and here is

when the psychological conception in the pulsation of the

space is interrupted, articulated and structured with

sequential acceleration of the rhythm of the space. With the

interruption of the continuity of the wall pulsation with a

structural reference and in parallel to the linearity of the

perspectival space focalized in the altar, Rainaldi

critiques Borromini’s spatial plasticity as a disciplinary

expansion.

Sixth, this linearity as well as the folding or the

Borrominean continuity are interrupted by a series of

frontal scenographic pictorial planes that perpendicularly

interrupt the perspectival cone, indexed by the columns and

the superior entablature of the capitals, as exaggerated

elements articulate the spaces with an undoubted Palladian

reference to structure[6]. At this point, we can relate the

effect of multiplicity in tension with the unification of

Brunelleschi’s perspectival space. The Borrominean pulsation

of the space is critiqued by an enfolding, as the Palladian

picture planes reinstitute a structural articulation.

However, it is due to the relative topological displacements

to the structural correspondences between the two spaces

that integrate them, that such particular polyrhythm unfurls

multiple visual and bodily affects.

Lastly, the columns as signs become unmotivated due to their

ambiguous formal functioning and to an overall structural

formal syntax, hence these differentiations are systematized

and contained within a field. The result is a complex field

that accelerates the space, folds, and that is articulated

within a pulsating continuity; but such continuity is also

simultaneously interrupted perpendicularly, without loosing

the perspectival unification that integrates the sequence of

columns. This field develops then two kinds of

differentiations, introducing an innovative idea that

creates a complex contradictory but simultaneously

progressive polyrhythm. These two differentiations can be

described as gradual rhythms that produce difference in

degree in the overall organization of the building, but also

as another kind of formal difference that critiques the

original organizational type of the building, that at a

conceptual level changes this original type into a the

deeper structural difference that enables many inverting

double readings and open relationships from these gradual

topological relative differentiations [fig.06b].

The double reading of a visual perspectival space and its

interruption by means of structuring pictorial planes,

generate an excess of multiplicity and a synthesis of

opposites in tension within a pulsating curvilinear and

folded spatial continuity [fig.04, 07]. This strategy

presents an affection that displaces a spatial structure in

a post manner, reintroducing a reference to a structural

re-composition that articulates and interrupts such

fluidity. Such movement presented as a mannerist

structuralist displacement, recomposes the whole through

perspective and the planes that perpendicularly interrupt

it.

These structural problems are precisely integrated with the

mediums of representation, establishing a manifest that

transcends the historic dialectic of the continuous state of

revolution in art between Renaissance and Baroque. The

building presents a spatial synthesis of many pairs of

concepts developed by Wölfflin simultaneously and in tension

that transcend the dialectic through a double negation –not

this not the other, not affirmative and negative- of a field

of relationships and tensions. Wölfflin presents the history

of art as a pendulum movement, a process in continuous

revolution, a dialectic between classicism and baroque as a

continuous historical structure. His categories: linear and

pictoric (tangible and intangible); plane and recession as a

spatial version of the previous one; open and closed;

multiplicity and unity; absolute and relative (clarity and

no clarity) left a box of tools that follow a Hegelian model

as Eric Fernie[7] suggests.

The space that Rainaldi is able to achieve is consolidating

this move against the alienation of the visual, as

structural relationships empower the presence of absence, a

pulsation that enables a spatial excess and a visual

awareness in a multiplicity. Thus is able to address the

media interfaces that striate the work recognizing such

mediation and therefore work out an architecture that

informs the visual from a structural logic.

The implied questions of this argument points to current

formalisms and their extreme automatization of formal output

that has been induced by the machinic diagram that now is

reaching a certain limit with algorithms. The formal

progressive differentiation generated by any machinic

diagram[8] should, to a certain extent, be more critical of

the relationships it produces, throughout the application of

a field intelligence that assigns value to the series of

iterations that such diagram may produce, re-editing the

outcome into a complex structure of reflexive operations in

order to overcome its predeterminations. If conceptual

difference is not critically introduced, structures remain

untouched, as it is the modern repetitive space of the grid.

Due to its flexible quality, the generic departing origin of

a diagram or a schema presents the possibility of developing

an abstract continuous topological transformation, a

genealogy of dynamic forces that accumulates traces by

indexing particular non structural mappings. This dynamic

topological transformation may enable such displacement that

may critique the point of departure, the recognition of such

a typological change that may induce a structural

transformation that as a critique of a transcendental type

enables a critique of generic concepts and categories. This

diagram is based on a structural flexibility that is able to

maintain the quality of certain relationships within a fluid

pulsating dynamic condition, consequently unlike the concept

of pattern in which repetitive units are based on a visual

appearance of unity.

NOTES:

[1] Original Drawings developed by students for the

architecture design II course Baroque Analysis directed by

professors Michael Young, Felicia Davis and Pablo

Lorenzo-Eiroa, The Cooper Union, 2008. Santa Maria in

Campitelli by Carlo Rainaldi floor plan drawing

interpretation by students: Sean Gaffney, Jess Russell,

Danny Willis, Malin Heyman, Liya Kohavi and Ge-nan Peng.

[2] According to Güthlein, Klaus, “Zwei unbekannte

Zeichnungen zur Planungs- und Baugeschichte der römischen

Pestkirche Santa Maria in Campitelli”, 185–255, 1990, in the

book titled Römisches Jahrbuch der Bibliotheca Hertziana,

München, Hirmer. In this article he traces several

archeological studies of the previous interventions and

possible alternative projects that constitute Rainaldi’s

church.

[3] Refer to Deleuze, Gilles, Nietzsche and Philosophy, The

Atholone Press, 1983, orig. France, 1962.

[4] Original Drawings developed by students for the

architecture design II course Baroque Analysis directed by

professors Michael Young, Felicia Davis and Pablo

Lorenzo-Eiroa, The Cooper Union, 2008. San Carlo by

Borromini floor plan and sections drawing interpretations by

Pamela Cabrera, Andres Larrauri, Rolando Vega, Elena Cena,

and Will Shapiro.

[5] S.M. Sette Dolori, Borromini, the space presents two

single spaces oriented functionally perpendicular to each

other with the benches, while the general organization of

the church follows a compressed layout that flattens out the

pulsation present in San Carlo.

[6] Wittkower analyzes in Palladio and English Palladianism,

the influence of Palladio (Veneto Region) in the Baroque

Rome. He quotes as an example the case of Bernini and his

colonnade in Piaza San Pietro in Rome, noticing the strange

combination of columns that are similar to the portico of

the Chiericati Palace by Palladio in Vicenza. On the other

hand, in relation to the picture planes used by Palladio:

“Rome has no precedent of a scenographic type of

architecture; scenographia, in the Palladian sense is

inexistent, including in the high Seicento. The type of

structures created by architects such as Borromini or

Cortona are basically antiscenographic...The architecture

based in an uniform system of elements do not produce a

concentration of motifs towards the altar. The contrary

happens with scenographic architecture, that does not obey

to that system...” Wittkower, Rudolf, “Carlo Rainaldi and

the Roman Architecture of the Full Baroque”, Art Bulletin

N.19, 1937. Even if at this point he does not mention the

case of Rainaldi, he clarifies that he was influenced by

Palladio.

[7] Fernie, Eric, art history and its methods, a critical

anthology, selection and

commentary by Eric Fernie, New York, Phaidon Press, 1995.

Article partially published in: